Dreams once buried beneath…sprout into undying gardens

Gabi Ncobo

It’s 2024 and Brazil is still burning.

In 1891, Brazilian officials across the country carried out an order from the Minister of Finance, Rui Barbosa, to systematically burn all documents related to 400 years of Brazilian slavery. After this attempt at obliteration of great proportions, Brazil introduced more policies aimed at erasing traces of Black people, who, by the end of the 18th century, had already formed the majority of the Brazilian population. As a solution to what has historically been referred to as “the negro problem”, Brazil adopted an ideology of racial whitening, a government policy aimed at increasing the proportion of the white population by incentivising and encouraging European immigration and interracial marriages. The widespread collective amnesia that ensued resonates to this day. Given the magnitude of the Portuguese slave trade, which is estimated to have brought more than five million Africans to Brazil, the burning of ALL records was always going to be an impossible task. The systematic erasure of Africans and the physical characteristics that distinguish us from other races was never going to achieve the full project of whitening the population. The quilombos that rose in defiance of slavery contain their own histories and practices that are present to this day and are emulated in community organising strategies and other practices of refusal.

“Has the fire read the stories it burnt?” is a question that guides chapter 0, of opera infinita, a multi-dimensional project by Denise Ferreira da Silva and Jota Mombaça. The pair poses this question as an “attempt at moving past reductive approaches that consider fire as an obliterant element.” This proposal calls for a different relationship to how the destruction of archives is mourned. Prompted by a fire that destroyed Indigenous archives at the African Studies Library at the University of Cape Town in April 2021, South African decolonial scholar Wanelisa Xaba asks us to consider “what it means to cry about ancestral knowledge kidnapped by an institution built on the bones of our ancestors?”. She suggests that we rather consider black and indigenous bodies as moving ancestral archives. She invites us to consider that our father’s nose is on our faces and that our mother’s wide hips and grandmother’s cheekbones exist as physical evidence of the endurance and invincibility of our ancestors as we move in the world.”

This is the angle in which I enter Dalton Paula’s practice, a practice that moves in and out of the constraints of the archive to create new possibilities that consider the interrelatedness of the body and the land as living archives. As a social architect of Sertão Negro, an Art School he founded in Goiás, Dalton engages collaboratively to raise from the ashes what history tried so hard to obliterate. He does this by inviting others to be actively engaged in the reimagination of their futures. The people that gather daily at Sertão Negro engage in emancipatory practices that help create spaces of ancestral healing through communing. The surrounding gardens operate as a laboratory of ancestral knowledge. Food is prepared consciously from what is grown on the land. The healing properties of plants, their ancestral use and their movement through colonial routes are some of the knowledge that are researched and shared. Music and cartographical movements sonically connect to histories of resistance of the African descendants who led anti-slavery revolts throughout the history of slavery in Brazil.

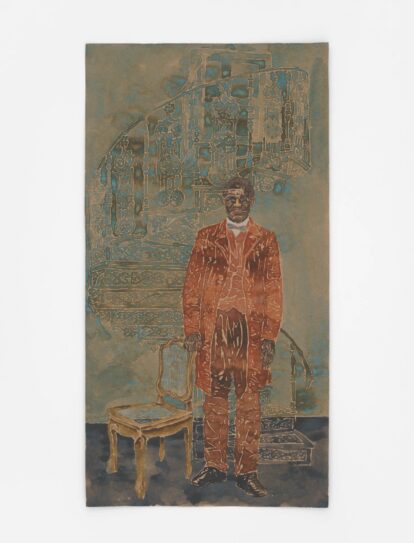

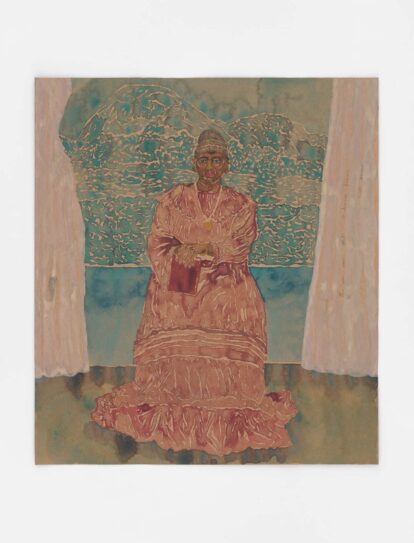

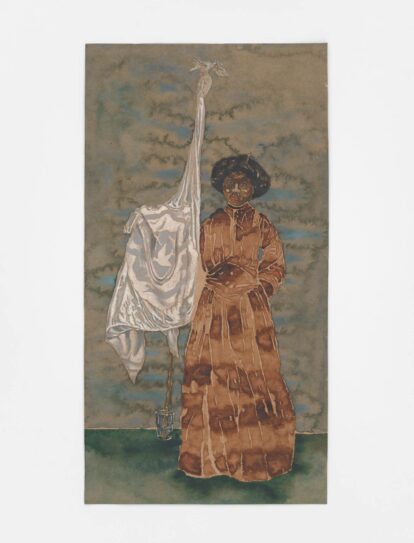

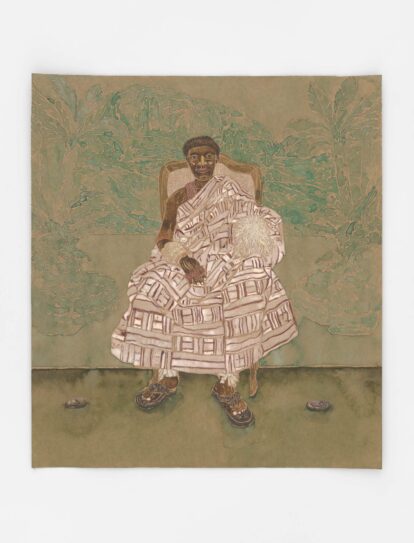

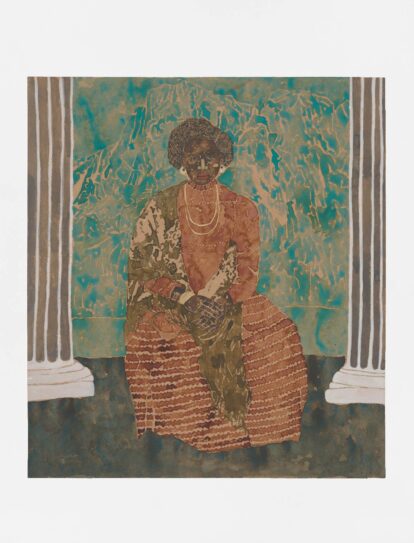

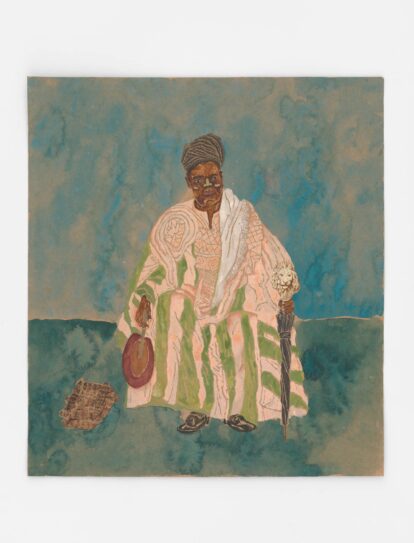

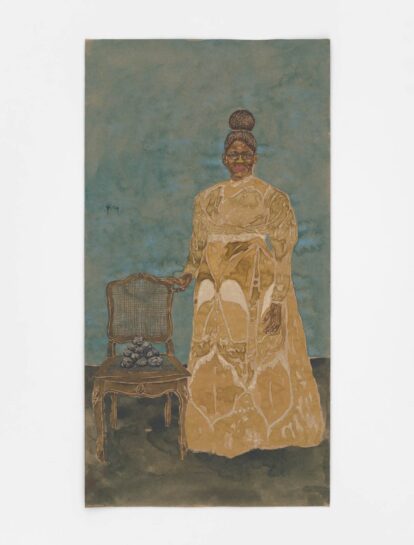

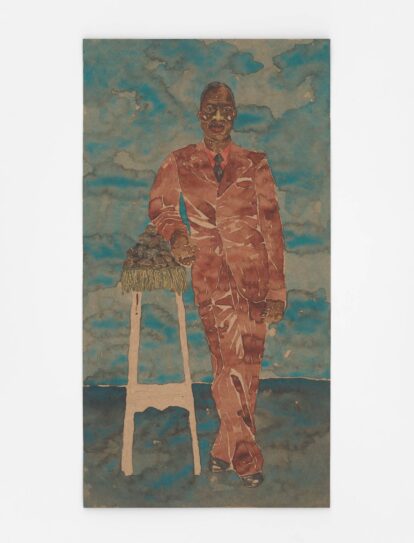

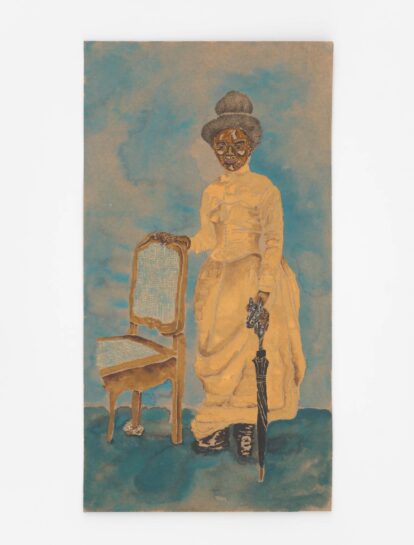

The critically fabulated historical figures brought to life by Dalton provide us with new possibilities for the ancestral archive. They emanate a majestic presence that is handled with meticulous care. Often plated with gold leaf, the hair becomes a symbol of wealth and resistance. By ‘crowning’ his figures, Dalton highlights the beauty and the history told through the texture and curls of the hair. The ‘crown’ always takes days and collective care to bring to life, one strand of hair at a time. The nose, painterly made more prominent, stands out gloriously in rejection of scientific racism that has, over centuries, used biology to justify the inferiority of Africans and other Indigenous people around the world. Dalton uses painting as a tool for unthinking the world; every fold on the clothes worn by the people portrayed, every background colour, and every object is present to communicate feelings and desires and to create associations. A simple glass containing water communicates its healing properties, stones that form a pile remind us of stones as used in protest, as well as emphasize our relationship to the land. Aqualtune, known as a leader of the Quilombo dos Palmares, holds a book, a physical symbol of knowledge and memory. All the figures are in poses similar to early studio photographs. In Dalton’s paintings, unlike in photographs, their poses soften to the medium and lose the burden of being looked-at-ness that photography often evokes.

The paintings in this series served as preliminary sketches to larger paintings currently showing at the 60th Venice Biennale titled Foreigners Everywhere. Their size and Dalton’s treatment of watercolours on paper gives them fluidity and the kind of spontaneity that wobbles the frame of history. They function as documents engaging with regeneration of cultural memory.

Reading of negative spaces in the treatment of the skin surfaces in Dalton’s work mimics the natural patterns found in plants, many of which can be found in Sertão Negro gardens. They read as cracks that exist in the formulation of histories. These cracks, however, do not need to be filled. They are there as reminders that what was lost can never be retrieved. They are spaces for imagining new possibilities where the negative can be transformed into infinite possibilities. Guided by the logic of the quilombo the Sertão Negro school is a testament to continued fugitivity and acts of refusal. It is an example of what can be brought to life if we take matters into our hands.

As the Amazon continues to burn, with 62.000 square meters already reduced to ashes in 2024 alone, we are always reminded that the global south still cannot breathe, and that breathing continues to be a privilege of class and race. By highlighting the nose, the passageway to the lungs, Dalton reminds us that fighting for the right to breathe is fighting to work towards ending the effects of the afterlives of slavery and colonialism. In her essay “Breathing: A Revolutionary Act,” Françoise Vergès reminds us that “The politics of unbreathing are historically racist, tied to capitalist industrial growth and environmental degradation.” In this reality, spaces such as those carved by Sertão Negro can serve as an example of continual resistance even as we pursue joy and pleasure in the things we are able to heal from and what we are able to harvest from what has been lost.