The urgency of intimacy

Martins&Montero is pleased to announce! The urgency of intimacy, an unprecedented exhibition that brings together two artists from different generations and contexts: Charbel-joseph H. Boutros (Lebanon, 1981) and Hudinilson Jr. (Brazil, 1957–2013). This is the first time that the works of these two artists are placed in dialogue, establishing a dialogue that opens new readings on portrait, self-portrait, and its aesthetic and political unfoldings. Although distant in time, space, and trajectory, both share the conviction that intimacy can be a starting point for traversing the world.

Hudinilson Jr., one of the most striking figures of his generation, worked with photocopy as if it were an extension of his own skin. By tirelessly reproducing parts of his body, distorting them, enlarging details until they became pure texture, he invented a radical exercise of self-vision in which identity dissolves in the act of seeing oneself. His body, in copy, ceased to be just body: it became a field of desire, of politics, of questioning the limits of representation. At the same time, his practice collected images and archives — from newspaper clippings to banal photographs of athletes or actors — in search of the points where male sensuality erupted in the cracks of popular culture. Hudinilson discovered sexuality and vulnerability in places where the common gaze saw only routine or entertainment, revealing the political potential of an intimacy exposed amid social conventions.

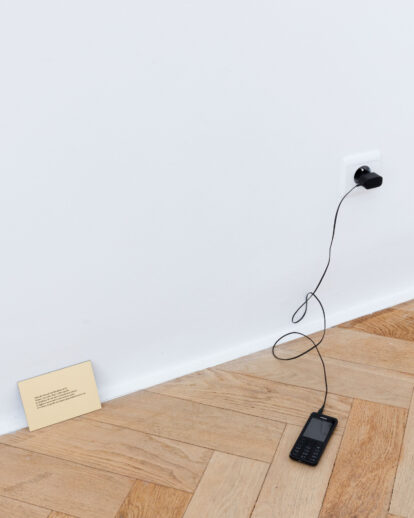

Charbel-joseph H. Boutros, a singular voice in the middle east and Europe, in turn displaces the portrait from its most immediate function. His works expand the genre into more abstract, poetic and conceptual fields, creating portraits not of faces and bodies but of layered elements. In Night Cartography for example, a brand-new bedsheet is used by the artist for one night, impregnated with his dreams. The next morning, Boutros collects that day’s newspapers, reduces them to ashes, mixes them with tap water from Paris and a binder, and immerses the fabric in this compound. The gesture transforms intimacy into matter traversed by the world: nocturnal dreams imprinted by the dust of collective events. The work is both a personal cartography and a societal portrait of historical time, simultaneously contaminated and illuminated by what surrounds us. In another work, Spring, a terracotta Jar made of 93 coils of clay — one per day, throughout the entire season — becomes the translation and receptacle of that season. From the outside, the piece is smooth, almost classical; like a funeral jar facing the collages of Hudinilson Jr., inside, it reveals its layers, as if it were possible to enter the interior of a memory. By adding invisible and unexpected materials (such as dreams, tears, fear, hopes, sweat…) to the physical body of his installations, H. Boutros opens a new territory in how art works are conceived and gives shape to unflinching portraits and the unquantifiable human quotient that lie behind what is tangibly seen. Such is clear, for example, it the piece 03 386051, a portrait of love, and death in which the artist presents his late father’s cell phone, a small object encased in his mother’s gestures of keeping that phone functional and charged for the past seven years since her husband’s passing. An installation created out of the real materials of death and love.

By placing side by side, the works of Hudinilson Jr. and Charbel-joseph H. Boutros, Martins&Montero proposes an improbable yet profoundly fertile encounter. The sensual force of Hudinilson’s body meets the poetic abstraction of Boutros, who expands the portrait into performative and conceptual gesture. If Hudinilson exposes the body as a territory of identity and revolution, H. Boutros presents dream, memory, and feeling as portraits of the invisible. In common, both point to the urgency of intimacy: not as withdrawal, but as a transformative force, capable of illuminating both the individual and the collective.

The exhibition invites the public to rethink portraiture beyond physiognomy. Here, the portrait is not just image: it is texture, archive, politics, memory, dream, and desire. It is a space of friction, in which intimacy expands and becomes an aesthetic and revolutionary experience.

Espelhe-Me / Mirror Me, Hudinilson Jr.

Simone Rossi

In 1983, Aracy Amaral—then director of MAC-USP (The Museum of Contemporary Art, University of São Paulo)—invited Hudinilson Jr. to participate in Arte na Rua [Art in the Street], a billboard exhibition in the streets of São Paulo. Hudinilson Jr. responded with a monumental xerox enlargement of his own glans. Before it could be displayed, the museum censored the work for its explicit sexual content. Rather than retreat, the artist folded the act of repression into the piece: he added a bold red stripe across the image, submitting it while exposing the institution’s moral boundaries. Around the neighborhood, street paintings appeared declaring Pinto não pode [Dick Is Not Allowed], amplifying the clash between desire and prohibition. The work, titled Zona de tensão [Tension Zone], staged the contradiction with crystalline force: the museum’s stripe inscribed the site of erasure, while Hudinilson Jr.’s street paintings mapped where desire overflowed into the city.

This episode encapsulates his wider artistic drive. Whether through woodcuts, street paintings, xerox, mail art, urban interventions, or collage, Hudinilson Jr.’s work sought not to conceal but to provoke. Desire and critique fused into a single impulse—toward awareness, transformation, and the undoing of taboos and everyday norms.

The street paintings may not be the most celebrated part of Hudinilson Jr.’s oeuvre. Yet they reveal another layer—colorful, pop, and resolutely two-dimensional. Each trace was a way of giving form to an urgent need to build a loving relationship: between the artist and himself, and between the self and the world. That urgency was born of a youth marked by denial and closure: on one side, the violence of a dictatorial and suffocating Brazil; on the other, the strict moral codes of a religious, middle-class, and heteronormative order.

Between the late 1970s and early 1980s, Hudinilson Jr. launched his first violent yet deliberate actions of symbolic-libidinal-haptic transformation—reshaping both the spaces around him and the ideologies that permeated them. With Mario Ramiro and Rafael França in the collective 3Nós3, he carried out nocturnal guerrilla actions that unsettled São Paulo’s official narratives: Ensacamento [Bagging] (April 27, 1979), when twenty downtown monuments were swathed in garbage bags—a surreal funerary gesture for colonial and state-sanctioned history; or X Galeria (June 2, 1979), when gallery doors and the entrance of MASP were taped with large “X” marks as manifestos declared: O que está dentro fica / O que está fora se expande [What is inside stays / What is outside expands]. For 3Nós3, the city was a blank sheet awaiting radical reassembly: a cuttable, rearrangeable surface where new experiential paths could be traced.

In parallel, Hudinilson Jr. pursued a solo street practice, channeling his obsession with reproducibility into the urban skin—an impulse as vital as the xerography that secured his reputation. He operated as the illegitimate heir to two formative influences: Regina Silveira, who introduced him to experimental research and underground networks, and the multimedia school-atelier ASTER (1978–1981), where he honed his skills in printmaking and engraving, techniques that would directly inform his urban practice, woodcuts, and xerox work. Though conceived as street works, Hudinilson Jr. carefully reworked many of these images into painting editions, translating their urban urgency into collectible form. In this double life, they remain rooted in the radicality of the street while inhabiting the space of painting.

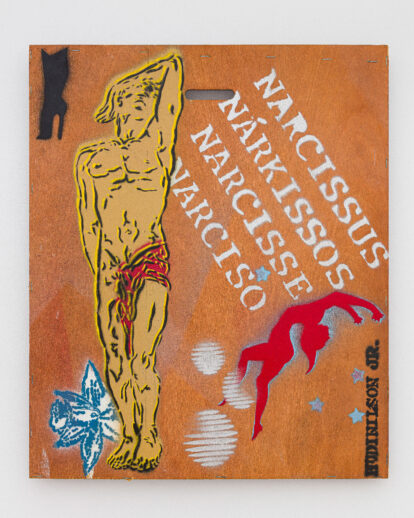

Through this urban practice, Hudinilson Jr. joined a clandestine brotherhood of artists weaponizing homoerotism, irony, and institutional critique. This network included figures like Claudio Goulart in Porto Alegre, who plastered the city with phallic images featuring heart-shaped glans as part of O.A.N.I / Objeto Anônimo Não Identificado [Anonymous Unidentified Object] (1979), while sending their ghosts through mail art circuits. In São Paulo, Alex Vallauri—a pioneer of Brazilian street art and a close friend of Hudinilson Jr. until his premature death from AIDS in 1987—was another vital reference. Vallauri bequeathed him both themes and techniques, most notably stenciling, a method derived from screen printing that Hudinilson Jr. would master. Yet, where Vallauri developed a kitsch aesthetic built primarily on consumer society symbols, Hudinilson Jr. injected three distinctly personal elements, forging a new lexicon from a vast repertoire of over six hundred images, all orbiting the same constellation of motifs.

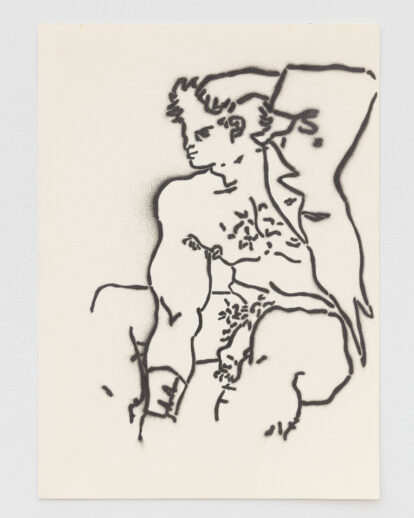

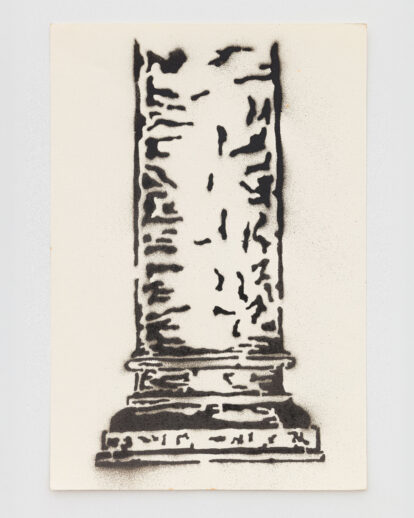

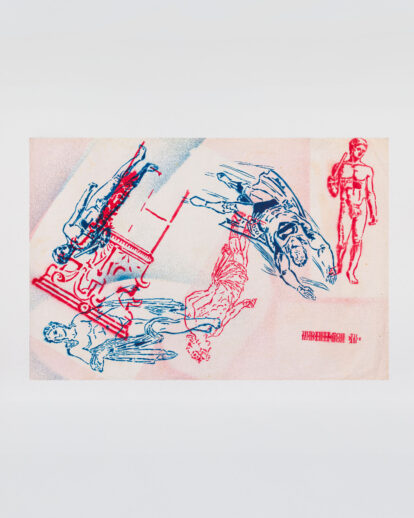

First, an explicit and targeted erotization: under his gaze, every image—from ancient Greek and Renaissance sculptures to comic book superheroes; from architectural columns to mythological figures like the minotaur and cupids; from portraits to explicit anatomical fragments—was transformed into an instrument of seduction and voyeurism. Second, provocative, tactile mottos: phrases like Espelhe-me [Mirror Me!] and Ahhh! Beije-me [Ahhh! Kiss Me!] undid fixed roles of observer and observed, issuing an open, collective invitation. Interwoven with tags like “Hudinilson Jr.” and “Narcisse,” these slogans became his urban signature. Third, and most profoundly, was the figure of Narcissus. The artist continuously convoked, adopted, and embodied this mythological topos. Through the lens of Narcissus, Hudinilson Jr. saw differently: Narcissus numbs the senses, reality turns psychedelic, a promiscuous interplay between gaze, body, and image where raw desire and the death drive cohabit.The two strands—collective intervention and solo street practice—were not separate but part of a single project of rewriting, what 3Nós3 termed interverção: to intervene and overturn. The city became a palimpsest, a canvas for inscribing new messages over obsolete, colonial, and conformist ones. These actions were not merely protests; they were letters to love, exposing the cruel joke of an authoritarian culture that treated queer desire and space as unutterable.

What emerges is an explicit, generative tension—provocative, politically engaged, poetic, erotic. This tension is the common denominator threading through Hudinilson Jr.’s entire oeuvre. His collages, and more broadly his Cadernos de referências, served as the resonant chamber for his entire poetics, housing all these experimentations at once; within these pages, the beholder can unravel the entangled trajectories of his thought and practice. To guide this process, Hudinilson Jr. leaves a clue: on the cover of Caderno no. 1, he glued a mirror—an intimate invitation to plunge into the abyss of Narcissus, an initiatory rite and a compass to finally embrace his gaze. It is the key to grasping the puta tesão [fucking arousal] that animates his urgent body-political, sexual, and affective subversion.