Garden Scene

Bernardo José de Souza

On the grass, a group of sculptures engages in an encrypted interaction, attempting to mask their artificial nature and, in doing so, acquire a life of their own. Misshapen, these figures transform into other entities and beings—chimeric, burlesque, tragic, or mythological: a drama staged outdoors, designed to disrupt the prevailing reality beyond the walls, rushing through the city streets. Defying the concept of nature seems to be the hidden purpose of these bodies, intruding upon a residential garden so that their grotesque forms appear even wilder.

The concept of nature—essentially a Western projection, whether scientific or romanticized—gains meaning only in opposition to culture, a constructed and therefore artificial world. Although so-called natural forms have been appropriated by culture over time—from Greek mythology to botany, and through agriculture, gardening, landscape painting, and art nouveau—the distinction between the spontaneous, untamed “natural” world and the rationalism that seeks to impose order, recreate, and classify it remains a touchstone in the West for conferring authenticity to any entity, whether organic, inorganic, or artificial. A prime example of this tension between culture and nature can be found in French formal and English landscape gardens, from the 17th and 18th centuries, respectively. The former rigorously and rationally controls plant forms, imposing order, and geometry—as with green mazes—while the latter seeks to emulate an idyllic, romantic vision, creating artificial grottos, simulating woods, and erecting faux ruins. In both cases, however, nature appears as an idealized form, shaped by human will—with humans distancing themselves from nature in order to exert greater control over it.

***

“Now, reality might have to interfere, at last.”

Charlie Fox

Drawing from landscape paintings, particularly Édouard Manet’s Le déjeuner sur l’herbe, Ana Mazzei creates her own highly distinctive version of 18th-century “conversation pieces”—paintings that depict groups of people engaged in an apparently spontaneous dialogue, set against wooded landscapes or interior spaces. As with all her work, the artist evokes an organic dramaturgy inherent to her forms, constructing a scene where various sculptures interact like characters in a Greek apologue, as if these inanimate objects possessed their own agency.

By placing her sculptures in a residential garden, Mazzei distances herself from the arbitrary architecture of exhibition spaces, casting her “actors” onto new ground in direct contact with “nature,” despite its domestic appearance. From the beginning of her career, the artist has explored theatrical devices, from their infrastructure—the architecture of stages—to their aesthetic and discursive expression: the proscenium. However, while the theatrical platform was once structured to incorporate sculptural pieces with a formal rigor imbued with silent, veiled eloquence, this time her sculptures escape the discursive severity of the “stage” to reveal their monstrous side in the open air. In Cena de Jardim (Garden Scene), what seems to be at stake is the very animality of the creatures presented, as if, distanced from the controlled space of the gallery, they were infused with their own souls, suspending their inorganic or artificial condition.

Although Mazzei has always confronted the artificiality of social spaces and the staged discourses of “actors” in her visual-dramaturgical orchestrations, in this exhibition she questions the very concept of mise-en-scène. It is as if her focus had shifted from the setting to the actors themselves, which Mazzei achieves by releasing them into “nature.” Clearly, this theatrical device only makes sense insofar as the very nature of her pieces is transfigured. In this exhibition, she moves beyond speaking exclusively about the human element invested in her geometric, architectonic-sculptural forms to touch upon the fundamentally animistic character of the creatures she engenders. Although Mazzei has previously explored the animality of design in her anthropomorphic works, the idea of nature itself now appears to take center stage. Under this new sign of theatricality, notions of humanity and of what is considered natural or artificial come under scrutiny en plein air.

***

“Political invention operates in acts that are at once argumentative and poetic, shows of strength that open again and again, as often as necessary, worlds in which such acts of community are acts of community. This is why the ‘poetic’ does not oppose the argumentative.”

Jacques Rancière

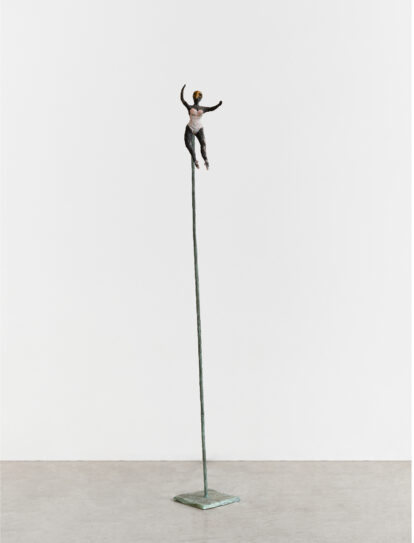

The fiction previously latent in Mazzei’s sculptures now emerges in the monstrosity of vaguely recognizable figures, born from a baroque hybridism that transforms a structure into a living body or, conversely, transforms a living body into a structure. By viewing the body as a construct, Mazzei disregards notions of nature and culture, presenting her sculptures as technologies of the imagination. Thus, the sequence of pieces in the garden calls for a political-semantic approach that distorts the strict notions of humanity or animality with which they are seemingly imbued. In Cena de Jardim, the human condition becomes subjugated by the power of its own design, or even by the force of its own imagination; or, perhaps, by the force of humanity itself, which attributes life or death to everything it touches, even if only on a philosophical plane. In this sense, the tiny, suspended ballerina is a marionette—both an object and a victim of her own dramatic-psychological orchestration. In fact, Mazzei has subjected the human element to the workings of its own designs before, as seen in the Garabandal series of chairs, which require the body to bend to the technology it has created—or when the artist dismembers the body, separating its parts, whether hands, feet, or heads, thus denaturalizing the supposed unity of the human form.

Mazzei creates a post-nature without any hierarchy between inanimate entities and living beings, free from an ontology specific to things that inhabit the tangible world—a concept taken to its fullest in the titles of the pieces. While some titles suggest hidden technologies within the piece’s deformity, such as Fone [Phone], others merely describe a shape, as in Aba [Tab] or Tripé [Tripod]. Instead of a semiological effort to distinguish signifier from signified, the titles draw from an immediate impression of the objects. Thus, Fone could just as easily be a dromedary, Aba a hair accessory, and Estrela [Star] a crown.

In a kind of trompe-l’oeil farce, the sculptural pieces resemble prosthetic creatures of varied constitutions, intertwined to create a fragmented calligraphy of organic and geometric forms. Wood—the artist’s preferred material until now, often used to emphasize a certain fragility and makeshift quality—is now juxtaposed with the solidity of bronze, whose colored patinas add movement and three-dimensionality to bodies in transition. Yet something human seems to have been lost in the process of creating these creatures. As perception dulls, qualities of solidity, perspective, anatomy, and dimension are abandoned, merging into a strange, trans-natural ballet. At times, the circus-like mise-en-scène of Cena de Jardim seems to mock the viewer, as if, for a fleeting moment, we were the anomaly—the foreign bodies in the garden—and these sculptures were the product of a nature more genuine than our own, the human species.

***

About the film:

In black and white, we watch the intuitive movements of a strange creature, part bird, part human. The figure navigates winding, rail-like lines, contrasting organic fluidity with technical form. Although infused with an animal-like psychology, the audiovisual piece evokes a Fellini-esque cinema—a melancholic atmosphere permeates both the landscape and the bird-ballerina’s body, merging them into one. The soundtrack injects a punk edge into the images, intensifying the clash between the supposedly human, animal, and artificial. Yet, communication between these seemingly inanimate spheres ultimately thrives: a bird recognizes itself in the avian-dancer hybrid, and vice versa, restoring the unity between culture and nature once again. Or perhaps not—on stage, after all, there is always a fourth wall, rendering life itself a work of fiction.