Thanateros: img_abstruction_666.gif

Fragments, Ruptures, and Enigmas: The Challenge of Meaning in Deyson Gilbert

Marcela Vieira

There are works that resist definitions rooted in the materiality that constitutes them, even though such materiality may be decisive in shaping a style. Nor can they be fully apprehended by means of the historical references coursing through them, even when summoned by the artist themselves. Neither are they reducible to the meanings derived from them, for meaning, after all, finds its counterpart—mystery—and from this association arise multiple possible readings that are anything but stable or established.

It is toward a complexity composed of dissonances—namely, assertive formulas and semantic impasses—that Deyson Gilbert returns after a prolonged silence in his own authorial production. It is worth emphasizing: a silence of production, not of activity. In recent years even while absent from the art scene as an artist, his presence has been felt in exhibition designs whose formal, poetic, and conceptual strength bears traces of his own language. This is the case, for example, with the exhibition Antonio Dias / Arquivo / O lugar do trabalho [Antonio Dias / Archive / The Place of Work], curated by Gustavo Motta and presented in 2021 at the Instituto de Arte Contemporânea (IAC), as well as with the solo show of Juraci Dórea presented in 2024 at Martins&Montero, Breveterno: notas para uma lírica político-mística da estiagem [Breveterno: Notes for a Political-Mystical Lyric of Drought], curated by Gilbert.

In Thanateros: img_abstruction_666.gif, the artist’s solo show currently on view at Martins&Montero, his unmistakable signature, distinguished by expressive aesthetic features, already unfolds in the very exhibition design. Its layout—marked by rods set at varying inclinations—suggests not only a guidance of the gaze but, above all, tension: rigid elements, likely upright and taut. Contrasting with the rods’ design, “points of weight” are distributed throughout the space, lending rhythm to the overall display. Accentuated by dark tones, such as leather laid out on the floor, and by textures, forms, and symbols of striking individuality, these elements embody a sculptural presence while simultaneously fulfilling a scenographic role. This is a matter of geometry, though not one of balance; instead, it is a composition of force fields.

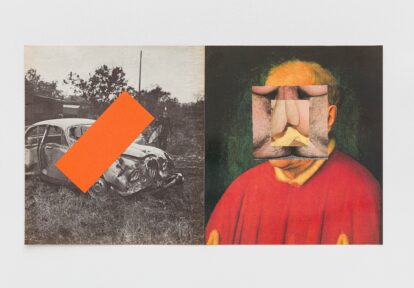

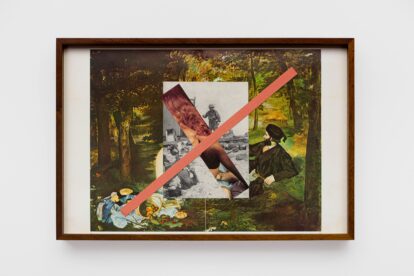

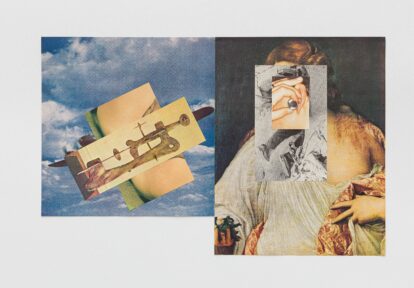

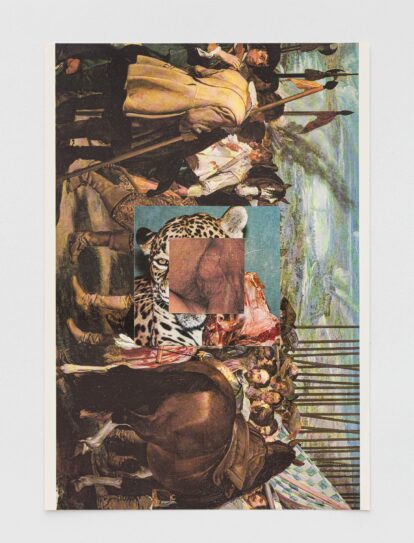

When approached as a “scene,” the space thus reaches a level of theatricality that both precedes and prepares the presentation of the works at Thanateros: img_abstruction_666.gif. These include collages, videos, leather rugs, cutouts from those same rugs affixed to the wall, sculptures, a live chicken, dead chickens, a mirror, a camera and security system, and serigraphy on tarps. Organized according to an intricate plan, these works compose a discourse that feels unified and cohesive when seen as a whole, primarily due to the rhythm imposed by the rods, the “points of weight,” figures in motion such as the live chicken, and certain installations suggesting movement. Viewed individually, however, these works open up enigmas of meaning, giving the impression that we are faced with a discourse grounded in a new language.

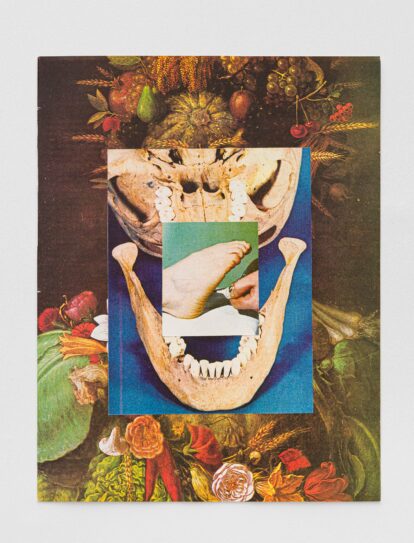

It is no coincidence that passion operators such as eroticism and death by crime stand together in composition literally fused to one another, more specifically entwining debauchery and torment. Thanatos, the personification of death in Greek mythology, and Eros, the god of love, are distilled into images arranged across numerous collages that allude both to the vital impulse of desire and to life’s inescapable limits—two themes governing human behavior at its ultimate threshold. Yet the death depicted here is not natural death but rather the death of war, provoked by the man-animal-political being capable of leading the body into the realm of the sacrificial, the victimal, and the sacred. Within this context, masculine gender and sex predominate in the visual representations, suggesting a phallic register made evident by the aforementioned rigid, vertical rods governing the space as well as by warlike connotations and homoerotic references that, at their core, amount to an insistent reiteration of the masculine.

In this set of works there is a constant concern with order—whether through display installation resources and the sequencing of images or through the presentation of sculptures that evoke scenes of penitence (the symbol of the cross is visible), sin, torture, and rituals, whether consensual (fetishistic) or not. This articulation once again brings eroticism into close relation with crime, and now also with the religious. Not even the chickens—living creatures—escape this dynamic: their lives are cut short to serve the visitor´s gustatory pleasure and the visitor, by consuming them, becomes a conscious accomplice to their death.

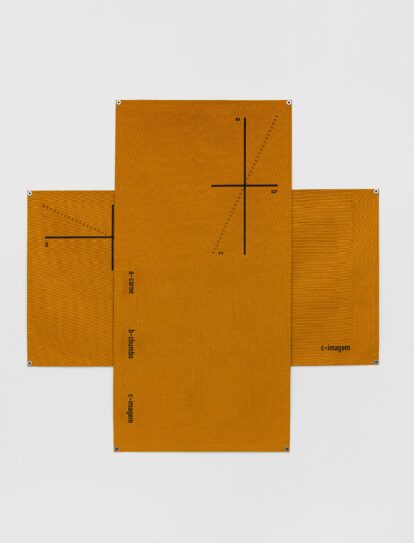

In Thanateros: img_abstruction_666.gif, triangulations can be hypothesized at vertices that articulate meanings without allowing them to fully close. One of these articulations manifests through the very titles of the works, which operate in three distinct registers: 1) the descriptive, as in the sculptures Figura ajoelhada [Kneeling Figure], Figura prestes a tombar [Figure About to Tip Over], and Figura caminhando em meio à tempestade noturna [Figure Walking Through a Nocturnal Storm]; 2) the referential, pointing to historical events, as in 11 de maio de 1937 (ou estudo para monumento ao Massacre do Caldeirão da Santa Cruz do Deserto) [May 11, 1937 (or Study for a Monument to the Massacre of Caldeirão da Santa Cruz do Deserto)], or referencing other artists, as in Piero della Francesca + Porn + Vietnam and Arcimboldo + crânio + chave [Arcimboldo + Skull + Key]; and 3) the conceptual, whose rules are offered to the viewer as a system to be deciphered, as in A – horizontal / B – vertical / C – repetição e diferença [A – horizontal / B – vertical / C – repetition and difference], in this last case, curiously enough, also conceived as a trinity. From this triangulation articulated through the titles emerges a correspondence between the registers of the real, the symbolic, and the abstract. If the sculptural and imagistic object can be understood within the realm of the real (image, figure), and the references the artist draws upon belong to the realm of the symbolic (culture, history), the third vertex points to a ritualistic order systematized and controlled by Gilbert, as revealed in the instructions accompanying these works—which, coincidentally, return to the image of the triangle: “Meditate on the triangle tacitly drawn between the pair of eyes embedded in your face and the anus’s cyclopean hole at the blind vertex of your buttocks.” Rather than closing off meaning this third “vertex” acts as a cut, an interruption that destabilizes the system and leads the viewer toward a point of openness governed by indeterminacy.

Speaking of titles, Thanateros: img_abstruction_666.gif carries in its very name a charge of irony by alluding to contemporary modes of image circulation. By evoking the GIF already in the title—a file format characterized by continuous, silent and fragmented repetition, widely shared across social networks and communication devices—Gilbert inscribes his collages of sex and war within the current visual regime, where images meant to wound or provoke desire circulate unscathed, immune to the violence or intensity they contain. The comfort we unconsciously attempt to resort when faced with such images, hastily scrolling past them, may stem from an impulse to domesticate whatever in them might unsettle us. Perhaps in response, the artist complexifies and radicalizes, refusing the automatism of the gaze and insisting on restoring density to vision, taste, experience, and ultimately memory.

War Garden – or Theory and Practice of the Drone

Gustavo Motta

There were some things called the pyramids, for example. […]

And a man called Shakespeare. You’ve never heard of him, of course…—The ethic and philosophy of under-consumption… absolutely essential when there was underproduction; but in the age of machines and nitrogen fixation, a genuine crime against society. […]—There was also monogamy and romance. Family, monogamy, romance. Everywhere the feeling of exclusivity, everywhere the concentration of interest, a narrow canalization of impulses and energy. […]There was also something called God. […]

■

All crosses had their tops cut and became T’s.

— Aldous Huxley, Brave New World

Target/Audience

Much like the opening scene of Bacurau (2019), Deyson Gilbert’s solo exhibition Thanateros: img_abstruction_666.gif, presented at Martins&Montero, first of all, offers the audience the point of view of UFOs—“unidentified violent objects” (in Grégoire Chamayou’s clever quip about military “hunter-killer” drones)[1]—scattered across the floor, zeroing in on the audience like miniature cyclopes. Besides, much like the opening scene of Cidade de Deus [City of God ](2002), the unlikely—perhaps even obscene?—presence of a live chicken with unpredictable behavior generates, amidst it all, a sense of disorientation that, partly because of the absurdity of the situation, induces in the audience a regime of cognitive alternation—a dizzying back-and-forth (albeit ridiculous, or, hopefully, ridiculed) between the viewpoints of prey and predator.

Shot/Model

In Fernando Meirelles and Kátia Lund’s action film this dynamic of alternation (between the chicken’s point of view and that of the armed mob pursuing it) is appeased through the introduction of the protagonist, Buscapé (a figure with whom the chicken becomes mimetically intertwined), and by the subsequent unfolding of the narrative in a sequence that brings together the main forces driving the plot: first the police, then a rival mob—a small gang from the “lek”[2] faction—all concretely or potentially armed, contrasting with but also analogous to the protagonist’s camera. The crucial point lies in the correspondence between shots—between photographing and firing—which establishes a technical and behavioral horizon of radical violence where seeing and killing become integrated. In the case of Cidade de Deus this correspondence formally accommodates the tension between points of view, transforming violence into an acceptable language through the aestheticization that permeates the entire film (including, aesthetically, the camera movements themselves), thereby ensuring its reception within commercial circuits.

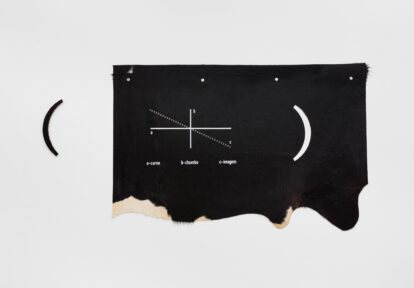

Flesh/Lead/Image

Although it shares with the film the figure of the chicken as prey and the socialization of violence (and, in part, its sublimation) in the preparation of a chicken stew, Thanateros: img_abstruction_666.gif proceeds differently regarding tensions of points of view. In fact, it asserts them radically through the systematic splitting of expository registers into three distinct material and spatial instances (following the triadic reasoning maniacally reiterated throughout the exhibition): A) the oblique plane of “flesh,” set in the performance/ritual/conceptual proposition involving the chicken and the audience; B) the horizontal plane of “lead,” comprising constructions and sculptural pieces; and C) the vertical plane of “image,” including collages and visual or televisual devices. There are certainly disparities and points of intersection where these planes merge and become indistinct—and like the live chicken named Image, they disorient the seemingly Cartesian frame of reference for these coordinates. What is worth noting is the unrelenting maintenance of this tension, which demands from the audience a systematic alternation between different cognitive regimes, aiming to de-automatize the experience.

Model/T

Regarding the historical horizon, Thanateros: img_abstruction_666.gif aligns with the sci-fi Western of Kleber Mendonça and Juliano Dornelles: both focus on the Brazilian backlands,[3] and particularly on the political-religious horizon of messianism.[4] In the case of the exhibition, this horizon is once again evoked on at least three distinct levels: A) Materially, in—just consider this—the engravings made on cowhide,[5] as well as in the steel pieces characterized by curved blades resembling sickles and machetes that share the floor with them; B) Thematically, particularly in the sculptural construction 11 de maio de 1937 (ou estudo para monumento ao Massacre do Caldeirão da Santa Cruz do Deserto) [May 11, 1937 (or Study for a Monument to the Massacre of Caldeirão da Santa Cruz do Deserto)] that organizes the space around which the smaller steel sculptures orbit; C) Formally, through a principle that can rightly be called esoteric, governing the meticulous ritualistic-sacrificial operation of the whole set, but more explicitly in Sobre o estrangulamento lógico de três galinhas (ou sobre, p. ex., um triângulo) [On the Logical Strangulation of Three Chickens (Or, e.g., a Triangle)] and its visual synthesis through diagrams shaped like

┬

which are nothing but a Greek cross

+

cut in half (like a Greek kiss given with just the lower lip).

Bull/Bullet/Bible

Broadly speaking, and to put it another way, despite their crucial differences, Thanateros, Bacurau, and Cidade de Deus accurately condense and share also three fundamental coordinates of contemporary experience: A) a historical dimension, or rather, a living tradition recognizable in the present—embodied by the violent figure of the jagunço[6]; B) a technical dimension, hyper-determined by devices that integrate seeing and destroying, visual culture and violence, entertainment and war; C) a socio-political dimension characterized by social disintegration, marked by a sense of apocalyptic rupture and, particularly in the cases of Bacurau and the exhibition in question, by political-theological discourses of a messianic nature.[7]

Totem/Taboo

Tensed by the disruptive violence of this contemporary constellation, that shared historical horizon also evokes a distinctive local—avant-garde—artistic tradition: while Bacurau revisits the thematic horizon and flirts with the allegorical procedures of Cinema Novo, Thanateros: img_abstruction_666.gif, in turn, cites and reproduces key processes rooted in the debate originating from the Nova Objetividade Brasileira [Brazilian New Objectivity] and Oiticica’s Environmental Program: the direct reference to Tiradentes: Totem-monumento ao preso político [Tiradentes: Totem-Monument to the Political Prisoner] (Cildo Meireles, 1970) through the immolation of chickens as well as the standard procedure of removing a part from a geometrized whole to render its incompleteness visible, emphasizing the violence of this operation—a procedure synthesized in Antonio Dias’s work in the form of collapsed rectangles, impossible to complete. Both are read here in a symbolic-sacrificial key (with their long-term political reverberations in Brazilian history). But unlike the Tarantinoesque—compensatory—catharsis of the Pernambuco neo-western, which aligns with classic blockbuster film conventions through the audience’s affective engagement with visual violence, inducing a cathartic jouissance[8] (as exemplified by Inglourious Basterds and action films in general), the exhibition in question instead imposes a suspension within that constellation of radical violence.

Repetition/Difference

This suspension re-signifies a structural procedure previously present in Gilbert’s work: whereas earlier the material tensions at the joints and points of support suggested instability and insecurity—as if the set of works were perpetually on the verge of falling apart, posing successive threats (whether virtual or real) to the viewer’s physical integrity[9]—here, in this exhibition, although the constructive principle largely remains unchanged and the viewer continues to be engaged in the presented play of tensions, the physical risk is now held at bay (with the reference to the earlier “sadomasochistic” game still present but somewhat distanced), relating to a judgment concerning the present status of violence and intimidation in political life. Given the issues under discussion, this suspension might be understood both as an instance of ecstasy and of critical reflection—or, alternatively, as a demonstration, yet to be verified, of a counterintuitive and unlikely but perhaps historically accurate nexus between these two instances.

Abstract/Concrete

The Brazilian modern experience—particularly that centered on the resistance to the 1964 coup—is, in this case, revisited negatively as an index of lack. As such, it serves as the foundation for a meticulous and unrestrained engagement with art history in general throughout this exhibition. In other words, materials drawn from the “great” history of art, especially modern art, are critically examined from a specific standpoint grounded in the periphery of capitalism, which assumes that historical processes are objectively embedded within artistic forms. On this basis, the modern art experience itself is approached through a fracture and thus mobilized by a clash between two vectors: A) One might call the first vector analytical-constructive: this includes Joseph Albers’ centralized squares in the collages; Malevich’s geometric and esoteric symbolism in the Greek crosses; the ubiquitous suprematist and constructivist diagonals; and the diagrams and linguistic games characteristic of conceptual art. B) The second vector might be termed negative-disruptive: it involves the tension of joints and lines of force that produce a critical reading of the constructivist and productivist “ culture of materials,” as well as the latent entropy in Formas Únicas de Continuidade no Espaço [Unique Forms of Continuity in Space], emphasizing the destructive element inherent in futurism; and finally, in the collages, the calculated and accurate absurdism associated with Dada and Surrealism.

Constructive/Destructive

There had to be a third vector, needless to say: C) that of the realm of reproducible images, namely explicit images of war and sex, triangulated—pardon the easy pun—by violence. Within this pornographic realm, it is also possible to include the pictorial tradition of art, particularly painting, which appears here in the collages through reproductions of works by Van Eyck, Piero della Francesca, Bosch, El Greco, Arcimboldo, Velázquez, Manet… drawn from the Gênios da Pintura [Geniuses of Painting] collection. These images function simultaneously as something at hand (like the central poster of an adult magazine)[10] and as an ostensive or explicit sign of culture—painting as “major art,” “the great reservoir of Western collective idealism,” a “true machine of sublimation,” and the “religious phenomenon that continues to parasitize the entire visual field of cultural discourse: the cult of painting.”[11] This explicit pornographic dimension of the collages—where human corporeality is reduced to the imagistic norm of representation—finds an analogy in the miniaturized anthropomorphism of the steel pieces (reminiscent, in their materiality, of the automobile era—and of futurism), which aligns the tacit but brutal threat of these watching/targeting objects with the systematic ridicule of the human figure noted by Adorno in the “little men and little women delivered to homes” through the small TV[12] screen (taken to paroxysm in the touch screens we carry in our pockets). Such symbolic debasement of the human body through reification—in which the body becomes property, at the mercy of its owner, like a toy—makes evident the technical trajectory that continuously links explicit sex or violence to artistic images, the Predator drone to the Bluetooth-activated dildo; the development of productive forces (in industry generally, cultural or not) as the development of destructive forces.

Aesthetic/Anaesthetic

And here, after all, Chamayou’s Drone Theory resurfaces in practice: in the massive rotating mirror/screen titled A – carne / B – chumbo / C – Imagem (estudo sobre a trindade [A – flesh / B – lead / C – Image (a study on the trinity)], which, integrated into a surveillance circuit, imposes, much like the UFO in the Bacurau scene, a literal (though importantly inverted) reflection and totalization upon the issues and materials mobilized and energized by the exhibition apparatus of Thanateros: img_abstruction_666.gif. To draw out the radical implications of how corporeality is approached in the exhibition, it is worth recalling Susan Buck-Morss’s use of Lacan’s “mirror stage” theory to propose a critical theory of fascism: the child’s triumphant recognition in the mirror image, followed by their narcissistic identification with and apprehension of themselves as a bodily unity—an imaginary unity, since it is visually projected in the reflection and therefore split from the actual body. In the terms of modern history:

In the “great mirror” of technology, the image that returns is displaced, reflected onto a different plane, where one sees oneself as a physical body divorced from sensory vulnerability […] “a space in which pain […] can be regarded as an illusion.”[13]

Combat/Slaughter

Returning to Chamayou’s central argument, the drone, when considered philosophically, is a device that provokes profound “crises of intelligibility” across several fundamental categories of contemporary social life. The first of these crises stems from the in extremis realization of the ballistic utopia that holds “the enemy can be struck from a distance before they are in a position to do the same,” which nullifies the combative disposition and warrior morality that, throughout human history, have animated the “art of war.” In practice, judged cowardly by the now technically outdated ethical model, “warfare, from being possibly asymmetrical, becomes absolutely unilateral. What could still claim to be combat is converted into a campaign of what is, quite simply, slaughter” [14] —the enemy reduced to a target.he condition for this is the “eye converted into a weapon,” the technical and political confluence between seeing and destroying.

Self/Immolation

The massive reflective device, along with the instruction (perhaps given by the artist to himself?) suggesting a specular meditation on “the triangle tacitly drawn” between the eyes of the face and the eye of the anus—echoing Mapplethorpe’s photography—indicates that, within a broader historical-social context, there is a reciprocity between A) the vector of forces that transforms the bidirectionality of war (combat/enemy) into unidirectionality (slaughter/target), and B) the one that transforms the former unidirectionality of Spectacle images (emitter/receptor, producer/consumer, author/audience pairs characteristic of traditional media like press, radio, and television) into the multidirectionality of images in digital media (embodied by the hybrid figure of the prosumer in contemporary social networks).

— C) Finally, we are capable of striking ourselves as if our physical body were not sensorily vulnerable, as if, in the position of predator, we were striking prey incapable of doing the same—as with the Image buried in the garden.

_________________

[1] See Chamayou, Grégoire. A Theory of the Drone. Translated by Janet Lloyd. New York: The New Press, 2015.

[2] TN: “Lek” is a colloquial abbreviation of the Portuguese word “moleque,” meaning “kid” or “young boy.” It refers informally to a small gang or group of youths.

[3] TN: “Backlands” translates the Brazilian word “sertão”—a vast semi-arid hinterland primarily in Northeastern Brazil, characterized by prolonged drought, erratic rainfall, and thorny, drought-adapted vegetation.

[4] Reiterating the investigative field of Juraci Dórea’s exhibition (Breveterno: notas para uma lírica político-mística da estiagem [Breveterno: Notes for a Political-Mystical Lyric of Drought], presented at Martins&Montero in 2024, and the text accompanying Marília Furman’s show Vazio e Dilúvio [Void and Deluge], shown at Central gallery in 2024, both curated by Gilbert.

[5] The term “engraving” appears here in its substantial sense, considering—again—three aspects present in these leather works, which share the title A – carne/B – chumbo/C – Imagem [A – flesh/B – lead/C – Image] (raising the question: could they be different editions of a single work?): A) the importance of incision in these works; B) the reproducible nature of the modules ripped from the leather, referring to cattle branding and therefore the herd (with its literal connotations in economy and metaphorical ones in politics and religion); C) the fundamental importance of their horizontal display. Regarding this last point, it is worth recalling Walter Benjamin’s preparatory notes for his essay on technical reproducibility, particularly the excerpt “Painting and the Graphic Arts” (1935-36): “Engraving has emancipated itself once and for all from the wall. One of the results is that the vertical position is no longer decisive for engraving. […] Painting projects space onto the vertical surface; engraving projects it as well, but onto the horizontal. And this is an essential difference. The vertical projection of space appeals only to the imagination of the viewer; its horizontal projection also appeals to his motor faculties. The spectator’s eyes anticipate his feet. The question is one of the correspondences linking engraving and painting with magic…, and of grasping the tangible differences between engraving and painting, and how these differences are manifested in the human body, for the body is the vital locus of the magical element. For engraving, the solution is not far to seek. The line whose magical power has always lain in the horizontal is that of the magic circle.” In Benjamin, Walter. Selected Writings, Volume 3: 1935–1938, edited by Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002) p.222.

[6] See in this regard the “revolution of the jagunços” and the “jagunço system” described by Gabriel Feltran in “The Revolution We are Living” available at: https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/708628?journalCode=hau

[7] I paraphrase, inverting the content of Perry Anderson’s framework that outlines the field of forces which engendered avant-garde culture at the beginning of the 20th century. See Anderson, Perry. “Modernity and Revolution.” In The Origins of Postmodernity, 97–130. London: Verso, 1998.

[8] TN: We chose to translate the original Portuguese term “gozo” as jouissance to accurately convey the concept from Lacanian psychoanalytic theory. Unlike ordinary “pleasure” or “enjoyment,” jouissance refers to a paradoxical state of intense satisfaction that often involves elements of excess, pain, or transgression, capturing the complexity and ambivalence of the engagement with violence as described.

[9] For a description of the procedure, see G. Motta, “Deyson Gilbert”, in Hans Ulrich Obrist, Gunnar Kvaran e Thierry Raspail (eds.), Imagine Brazil (Oslo, Astrup Fearnley Museet / Lyon, MAC, 2013), p. 54-59.

[10] See the remarkable analysis of the playful and handheld nature of the central poster in Playboy magazine by Paul B. Preciado in chapter 3 of Pornotopia: Playboy e a invenção da sexualidade multimídia (São Paulo, n-1, 2020). TN: The original book was published in English as Pornotopia: An Essay on Playboy’s Architecture and Biopolitics (Zone Books, 2014). The Portuguese translation emphasize “the invention of multimedia sexuality.”

[11] “The ideological tutelage over the pictorial image reaches its apex with Classicism. One can thus speak of a criminal enterprise, as this involves a true strategy of standardizing the body, where gesture, pose, and physiognomy are subject to meticulous conformity control: aesthetic norms are merely the socially acceptable mask of a deeper social demand. […] But this is nothing compared to what follows. Winckelmann pushes the system to its extreme limits. He transforms the figure into an idea: denying expression, passion, and movement. Hatred of the body. The constant aim is to negate it. Western art tends toward nothing else.” This passage is from Régis Michel, La peinture comme crime – ou la part maudite de la modernité (Paris, RMN, 2001), p. 6. TN: No official English translation of this excerpt is currently available. Our English rendering follows the Portuguese version appearing in this essay.

[12] “[…] the miniature format of human beings on the television screen was supposed to hinder habitual identification and heroization. Those on the screen speaking with human voices are dwarfs. They are hardly taken seriously in the same way that characters in film are. […] The little men and women who are delivered into one’s home become playthings for unconscious perception. There is much in this that may give the viewer pleasure: they are, as it were, his property, at his disposal, and he feels superior to them. In this point television borders on the funnies […]. Such discrepancies permeate all products of the culture industry and recall the deceit of the doubled life.” Adorno, Theodor W. “Prologue to Television.” In Critical Models: Interventions and Catchwords, trans. Henry W. Pickford, 49–57. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), p. 51.

[13] Susan Buck-Morss, “Aesthetics and Anaesthetics: Walter Benjamin’s Artwork

Essay Reconsidered.” October 62 (Autumn): 3–41. (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press,1992), p. 33.

[14] Grégoire Chamayou, A Theory of the Drone, trans. Janet Lloyd (New York: The New Press, 2015), p.